Thursday, 27 October 2022

Hot sun and cake

Wednesday, 26 October 2022

The Angry Birds of Lublin

I have not read much Polish--just headlines here and there--since I fell ill at the end of September. The brief bout of what the stick afterwards told me was COVID seems to have left me reluctant to study. I would not say it was the last straw, but it has given strength to the little voice that says, "Why bother?"

And the moment has come to write about the trials and tribulations of studying Polish in Lublin, which contained not only the difficulties to which post-Soviet workplaces are prone, but the nastiness of fellow foreign students of Polish, most of whom were more than 20 years my junior.

When I arrived at the student residence, after a long and solitary journey involving a plane and a train, the porter had no record of my existence. Although I was disappointed, I was not surprised. The organiser of the course had sent me emails about my studies only when he was reminded with a phone call. Years of experience of travelling in Poland led me to sit down and let the porter sort it out. He did. So far so good.

But I had no internet connection, I discovered, and the porter couldn't sort that out, so I wondered what to do. As I was going up the stairs, a group of women in their twenties swept past me, chatting in American.

"Girls," I said cheerfully in Polish and then, Polish deserting me, I foolishly said, "Are you Americans?"

"No," one shouted up the stairs scornfully, and I could have kicked myself. Five years of working online with Americans had made me forget the essential (and hypocritical) anti-American streak in Coke-drinking, Disney-watching, American-speaking European (and Canadian) life. Another said, more honestly, that they weren't all American.

Dropping the American theme, I asked them if they knew the wi-fi password, and they told me, in surly, suspicious tones, that I should have got it in "the email."

And off they went.

I have given this a lot of thought, and I suspect that was my Devastating Social Error Number One. Devastating Social Error Number Two happened the next morning, at around 6:30 AM, when I dropped a metal French press full of coffee in the small vestibule outside my door and that of the women in the next room. (We shared a bathroom.) I was tired, burned and furious with myself. From the other room, there was not a peep. I cleaned up--and there was a lot to clean up--and determined to apologise to my neighbours as soon as I saw them.

But I didn't see them for days, and when I did, they didn't acknowledge my existence. In fact, I only realised that one of them was my neighbour after I recognised the scarf hanging in the vestibule as belonging to the rainbow-haired young lady who had been flirtatiously contemptuous (I thought) at a handsome young priest. (He was a seminarian, actually.) I was shocked, and it may have shown on my face, which would have been Devastating Social Error Number Three.

Devastating Social Error Number Four was habitually turning off the light in the vestibule, for which there was only one light switch--by the hall door. I realised my mistake only when my rainbow-haired neighbour swept past me and turned it off as I was unlocking my bedroom door.

"Hey," I shouted.

Slam went the hall door.

This young lady, whom I will call Gerta, was American and had such a large, prominent and distinctive tattoo that if I described her, you would recognise her immediately upon meeting her. Therefore, I'm not going to describe her but leave this for a novel I will write in the tranquility of my old age. (Dye stains on towels left for Housekeeping will feature.) What I will say is that she didn't speak to me or respond to my greetings for two weeks.

I was so rattled by this silent treatment that eventually I broke down and cried in front of my 22-year-old private tutor and sobbed out (in Polish) my feelings of isolation and rejection.

Because it wasn't just Gerta.

It was the Slovenian girl who asked, her voice dripping with contempt, why Polish- and Slovenian-Americans were so interested in Polish and Slovenian culture when, in Slovenia, it was more cool to be foreign.

It was the American boy whose every word to me was a verbal eye-roll.

It was definitely the young woman from somewhere or other in Europe who actually made an "ugh" noise at the back of her throat when I wished her a good day.

It was also the Montrealer whose "I don't want to talk to anyone from the wrong part of Canada" declaration and jokes about "boobs" did not reduce his popularity with Generation Z an iota.

And it was the female passerby who smirked when all Polish deserted me when I was downstairs trying to talk to the porter.

It was also, in a lesser way, the organiser of the course who could not be bothered to add my email address to the list, or come up with an alternative list for those who would be at the school in August. Or for those who weren't university students.

Every day for two weeks I was blanked and blanked again. I felt like the big ungainly fowl who interrupts the little birds by landing on their own personal telephone wire, only without the sense of humour.

Because, even keeping in mind my active mistakes, I realised that the Most Devastating Social Error of All was being a woman over 40.

(And in case you are wondering if they had all Googled me, I was there under my maiden name.)

That I wasn't utterly miserable is thanks to the friendly personality of a half-Polish Italian girl in my homeroom (as it were) and, especially, a 50-something Polish-American civil servant I'll call Stan. (Hi, Stan!) The Italian girl and I didn't speak much outside class (she lived and lunched with Polish relatives in town), but she smiled and acknowledged my existence. Stan chatted with me and the other old lady in the dining hall, a melancholy Poland-loving Central European widow. It turned out that her melancholy was partly due to Gerta, who had been her great pal last summer, but was now blanking her.

I am very grateful to Stan for enlivening a lonely time. His previous stay in Lublin was during the Cold War, and he told me all about what the city looked like then. Stan has family in the Tatras, near Zakopane; he told me about Goral hospitality and family ties and how his late grandfather, who spoke no English, gave him an American $20 bill. Stan really really believes in American democracy; he also told me about what he had done to preserve it.

It was Stan who told me where the nearest weight room was and where the best cakes were. He also attempted to harden me up to the realities of life as the next-door neighbour of Silent Treatment Gerta by saying, "Are you going to let a 22 year old girl upset you that much?" That said, he was annoyed and disgusted by another a young American, a man who bragged so much and was so self-absorbed that he was positively iconic. You couldn't make him up. Stan couldn't stand him; I valued him as a future character in my next novel.

And I will say this for Frank (not his real name): he was not an age snob. Although he never asked us about ourselves, he didn't make "ugh" noises or roll his eyes or blank us. And when (Week 3) I was exclusionary myself, asking Stan at the one lunch table of remaining students if he were free for cake later, Frank didn't sneer. As the group of students got smaller and smaller, he just asked whoever was left if he wanted to go out for drinks.

Stan, a Democrat, looked up my workplace but was quite openminded about it, possibly because he had been cold-shouldered or cancelled for not always sticking to the party line. Apart from being Generation X and Catholic, what we had in common was a wistful desire to improve our Polish and the notion that it would be a great retirement plan to live in Lublin all year and study Polish every day. The teachers, at least, were very good, and Stan had not been as neglected by the organiser. For example, soon after he arrived, a beautiful young Polish girl popped up before him and announced, "I'm your angel!"

"Yes, you are," thought Stan, but it turned out that the angel's job was to make sure he didn't get lost, had everything he needed, etc. (Where was my angel? Well, I guess he was Stan.)

This post is for Stan, who told me to contact him when I wrote about the course. I suspect he was hoping I that I would lay waste to Frank, but I don't want to squander the rich possibilities of Frank, the millennial Rex Mottram, in a blogpost. Frank deserves a novel, and I'm sure Frank would agree.

Meanwhile, now that I have gotten the Angry Birds out of my system, I think I will later write a happier blogpost about Lublin, this time stressing the loveliness of the actual Poles (except the organiser), the splendid cafes, and the delicious farewell supper I shared with Stan.

In case you are wondering, Benedict Ambrose is also grateful to Stan. Once I got my wi-fi sorted out, B.A. had to listen to my trials and tribulations every night. "I had cake with Stan" was a nice break from "All the twenty-somethings hate meeeee!!!!"

Message for Stan: I first wrote about it here.

Friday, 21 October 2022

Sufficient Unto the Day?

|

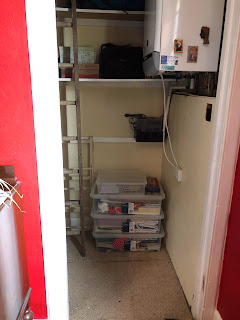

| Actual British boiler in a weeny flat |

The plumber is coming, so I have been tidying up and thinking about my late, great friend Angela who used to talk wryly about "cleaning for the cleaner." Now I am thinking about those lovely little robots that do the vacuuming and how much buying one would disrupt our savings goals.

I think about money quite a lot these days, in part because I enjoy doing simple sums and thinking about how we guessed right in (A) overpaying the mortgage (B) locking in a fixed rate mortgage before even the lowest ones soared above 2%.

The alternatives were, of course, spending more on our "Lifestyle" or shoving the money into the Stockmarket. Until recently, financial independence bloggers often compared the great gains you can make on the Stockmarket versus the relatively low percentage everyone seemed to be paying on their mortgages. They would warn against "opportunity costs" and talk about making 6%-10% on your own money in the markets versus the 1-3% you had to pay on the bank's money.

Naturally, banks don't loan ordinary folk hundreds of thousands of pounds/dollars to put into shares, so in a bull market using the bank's money to finance your home while you make a killing with your own money makes sense. But that sounds all very 2009-2019 to me. Since Spring 2019, we in the UK have had Brexit, the COVID lockdowns, and three prime ministers. The markets are down, the pound is down, inflation is up, and mortgage interest rates are up, too. Oh, and so are gas and electric and rents.

Buying a weeny, well-insulated flat far from the city centre and throwing money at the mortgage as if bailing water out of a sinking boat turned out to be very smart. And this reminds me that even if money cannot buy you happiness, it can buy you a certain peace of mind.

This in turn reminds me of Matthew 26:6 - 34 ("Behold the fowls of the air...") which in turn leads me to wonder what the Lord meant about not worrying about food, drink, clothing and tomorrow. (I shall send a text to a seminary professor friend to ask.) Perhaps He literally meant that we should not feel unhappy about the food, drink, clothing and tomorrow issues but just do what we're called to do (which usually means paid work of some time or keeping house for your salaried spouse) and trust in the Father to make things work out ultimately for the best.

I wonder if schools now teach children and teens about money, the miracles of compound interest, and the joys of capitalism versus the evils of consumerism? When I was an undergraduate at the University of Toronto, it was still fashionable in some circles to be rude about the bourgeoisie and capitalists, but I would guess that a large percentage of the students born in Canada sprang from the bourgeoisie and that their parents owned capital, if only in the form of their houses. (Today the average house price in Toronto is over a million.) Thinking back to the 1990s, it seems to me that the children of immigrants were less likely to be rude about capital, perhaps because they knew how much work it takes to get it.

It strikes me this puts the children of immigrants to Canada at a psychological advantage. They know where money comes from, which means they know where to get it, and how hard their parents had to work to earn money, which fosters gratitude and loyalty to their parents. Second, they might also understand why it would have been even harder (or impossible) for their parents to get the money in their countries of origin, which fosters gratitude and loyalty to their new country.

I'm thinking not so much of immigrant kids of my own generation but of Millennial Revolutions' Kristy Shen and Bryce Leung. Toil do they not and neither do they spin because they took degrees that would land them high paying jobs, saved as much as they humanly could and retired as millionaires in their early thirties. They don't worry about food, drink, and clothing but live within their means, keep an eye on their aging parents, chat with likeminded people from around the world and travel like the unusually energetic Canadian retirees they are.

Their book doesn't mention this, but I am relatively sure Shen and Leung didn't spend their time at university shutting down other people's freedom of speech.

And now about that night at Edinburgh Uni

My keenest readers will know that I was at Edinburgh University on Monday night to report on a lecture by a speaker from the Society for the Protection of Unborn Children. They will also know that this lecture was attended by a hostile group carrying banners and interrupted by a second (but related) group carrying a bullhorn. The blue-haired holder of the bullhorn made a speech which could have been a parody of such speeches, carefully mentioning "people with uteruses" instead of women, and saying that the students who had invited the speaker didn't "deserve a platform."

The odds are the blue-haired woman was American, but there was something about her voice that made me think she might be Canadian. Either way, leading an occupying army into a room to stop a woman from speaking was an atrocious way for someone to behave in a foreign country. I would not have been thrilled had a Scot led the charge, but I might not have been so angry.

I was also angry at the self-righteousness of the occupiers who shouted "Who funds you?" at the SPUC speaker, apparently believing (despite their own American members) that there is something particularly disgraceful in receiving donations from Americans. (In reality, SPUC is mostly funded by British donors, and in Scotland I would guess the majority of them are working-class Catholic Scots.) Their unshakeable belief that--at a university, at Edinburgh University--they were entitled to stop an audience from hearing a speaker they had come to hear--was appalling. I was also angry at the sense of entitlement of these shrimps, especially when they expressed how "f****" angry" they were against Edinburgh University as if it were their own ungrateful child who had let them down.

I was also scared, both for the security of my phone (with which I was recording this disgraceful scene) and for the speaker. When I was in my twenties, pro-abortion demonstrators could be damned violent and in 2012 someone tried to murder people working for the Family Research Council because he didn't like the FRC's stand on gay marriage. (He succeeded in killing the security guard.) I got a young man I know from church to walk me to my bus stop after the fracas, and I ascertained that the pro-life women I thought most at risk were similarly protected on their way home. (To be fair to the Gen Z mob, thoughts of physical violence may never had entered their university-enrolled heads.)

I was so angry that, not only did I not sleep until 2 AM on Tuesday morning, I woke up at 6 AM on Wednesday. I realised then that the only way to exorcise my fury was to return to my "platform." At the meeting I couldn't say anything because I was reporting on the incident, but afterwards--let's just say I made full use of Article 10 of the Human Rights Act 1998.

When I had written this second article, gone to the gym, and returned home to begin my real working day, I reflected that not only do I have a "platform" to express many opinions the occupying activists wouldn't like, I get paid to express them, too. It was a very cheering thought.

Sunday, 16 October 2022

The Care and Feeding of Husbands

|

| Don't let him eat this more than once a year. |

First, I must declare that I am not a doctor (even of theology) and that random posts by church tea ladies should not be read in lieu of seeking proper medical advice.

Second, I regret that this will not be a particularly intensive article.

But, third, I also point out that all men--despite being the same in some respects--are unique, each carrying a wondrous galaxy within. Therefore, the SAHM (stay at home mother) and other wives in general (why do we not say SAHW?) will have to think about her own particular man whenever weighing up advice about the care and feeding of husbands.

Incidentally, not too long ago it was common for a Scotswoman to refer to her husband as her "man," and Scotswomen--after getting past initial greetings and remarks about the weather--would say "How's your man?" Now they seem more likely to say "your partner," and I no doubt cause offence when I say, "My husband is very well, thank you."

1. Medical care

My husband is very well, thank you, and not six feet under because when we first married, I signed him up at the medical clinic charged with the care of our geographical area. I was surprised to discover that I could do this until I read that, in general, men in Scotland don't go to the doctor unless their wives (women, partners) send them. The male reluctance to go to the doctor is apparently one of the reasons why men-in-general die before women-in-general do.

Therefore, I recommend to the starry-eyed young bride to find her husband a family doctor (or sign him up at the neighbourhood clinic) as soon as the honeymoon is over. If he hasn't had a physical in some time, it might be a good idea for him to have one now, just as you're starting out. You might want to have one, too.

Naturally, suffering may be involved. The overweight nurse who weighed me told me I weighed too much, and she told Benedict Ambrose that he drank too much. However, the sting wore off when I realised that 60% of women in Britain are overweight or obese, and 26% of men in Britain drink more than the recommended 14 units per week. More on this anon.

2. Man flu, etc., should be taken seriously

My mother has never made a joke at my father's expense, and I was quite advanced in age when I came across the phenomenon of women mocking men for "man flu." The idea is that men lack fortitude and make the most of their minor illnesses so they can do even less housework/childminding/yardwork than ever, ha ha. But it turns out that men might actually, objectively, suffer more from minor illnesses because they have weaker immune systems.

Having just come out of a rather achey bout of COVID (which I thought was flu and through which I breathed as freely as a zephyr through the woods), I cannot think of anything crueller than mocking someone suffering from an illness so badly that they take to bed.

Meanwhile, my own husband is still alive because I took his aches (behind his eye, in his neck) seriously and said, "You should see the doctor" and "You should reschedule that cancelled eye appointment." Of course, it was not just me. Benedict Ambrose was also saved by the late food critic A.A. Gill, who wrote that the first sign of his terminal cancer was a pain in his neck.

Therefore, I also recommend to the starry-eyed young bride that when her husband confesses to her that he has a strange shortness of breath/recurring angina/a pain in his neck/a pain behind his eye/recurring migraines/a lump or any other weird thing that she say "You should see the doctor" and then, if he does not make an appointment, to make an appointment for him and inform him where and when. If necessary, drive him.

3. Meet your sick husband's primary caregiver: you

Should your husband end up in hospital, God forbid, visit him every day, get to know the people caring for him, and don't take COVID for an answer. (I don't myself know how to do that, mind you, and I often thank God B.A. recovered by 2019.) At any rate, try to be privy to all conversations about his medical care, and go with him to appointments if you are in the slightest doubt of his current mental capacity or ability to communicate clearly.

I don't know (of course) how things are where you live, but the National Health Service in Scotland was very stretched, even before the COVID crisis, and it was obvious to me that whereas nurses and doctors had to divide their attention among dozens of people, I had the advantage of being able to concentrate on only one.

Had we had children, by the way, I believe I would have sent them to family in Canada during this period--or imported my own SAHM to watch them.

4. Praise

As I have blogged many times over the past 16 years, my mother constantly praised my father to their children. This means that it feels easy and natural to praise my husband. Of course, my husband is also very praiseworthy individual, but presumably even the good-enough husband does praiseworthy things like wash the dishes, take out the rubbish, bottle the apple cider, call the plumber and all those other things you would have had to have done had he not done it.

I have a theory that men need praise more or less in the same way they need food, so if you want to help keep your husband mentally and physically healthy, you should thank him every time he does some household task, tell him he is clever whenever he does something clever, and applaud him for anything he rather thinks he has done well.

This also has a good effect on wives. I once had a very sad email or comment from a young reader who wrote that she couldn't stand to go to bed with her husband because she could no longer respect him. I do not at all know their circumstances, but it occurs to me that if she heard herself thanking him daily for such simple and mundane things like putting his dirty socks in the hamper or applauding his ability to throw an apple core into the trash bin from 12 feet away, she might not feel that way.

Fifty years of propaganda have led me to believe my dad is just a little less than the angels, and fourteen years on, I am pretty sure B.A. is reaching dad-like heights. Is all this rooted in reality or in brainwashing? Hmm. Either way, my dad and my husband are both still alive.* Yay!

5. Example vs nagging

People are very much influenced by the people with whom they spend the most time. Therefore, if you are determined that your husband should have healthier habits, you should first adopt healthier habits yourself. During the COVID lockdown, when my health club locked up, I bought an exercise bike. I kept it in the kitchen as a reminder to exercise. I pedalled away and was absolutely delighted when my never-caught-dead-in-a-gym husband began to pedal away, too.

Another healthy habit to consider is giving up alcohol on the same days you give up meat, should you be the sort of Christian who both drinks alcohol and periodically abstains from meat. If you announce that you are no longer going to drink alcohol on Wednesdays and Fridays, your husband may decide to join you in that. (To be honest, though, I think Benedict Ambrose and I came up with that idea together.)

So much for alcohol and fatness, the twin devils of the NHS (see above). Other healthy habits you can take up include eating at least 5 vegetables (and fruit although vegetables are now said to be vastly superior) a day. If you are in charge of cooking, you have a lot of control over what your husband eats. If you yourself smoke, you should stop. If your husband smokes and refuses to stop despite everything doctors, scientists, his mother, his sisters, his teary-eyed children, and you have to say about it, you can at least set limits like "not in the house" and "not in front of the children."

But I don't have very much experience with nicotine addiction because my smoking grandmother quit cold turkey after landing in the hospital with double pneumonia. To this day I associate cigarettes with nervous but affectionate old ladies with long crimson fingernails, and when men ask me if I mind if they smoke, I usually say, "Oh, not at all! It reminds me of my grandmother." This never fails to annoy them, which I don't mind. In fact, I hope it makes them so self-conscious they quit because--I haven't had an excuse to type this in years!--men are the caffeine in the cappuccino of life.

*UPDATE: All joking aside, your husband is going to die, and unless you murder him, it won't be your fault. (See yesterday's post.) God will call him to Himself when He sees fit. However, I feel that there is some room for negotiation with the Most High on this matter.

Saturday, 15 October 2022

Advice for prospective young SAHMs

|

| Suitably lonely looking road. |

Before I go any further, a SAHM is a "stay at home mother," o readers who are not acquainted with Christian lifestyle disputes on Twitter.

Occasionally I go over my past to find my life-changing mistakes: a terrible, demoralising habit. It is tempting to think that everyone else was handed a foolproof template of "What To Do and How To Do It" by their parents when they were 16. I am now inclined to think that almost everyone in my generation (X/Y) just stumbled from this imperfect decision to that, backtracked, leapt forward, and generally found themselves on a life-sized game of Snakes and Ladders.

It has become a cliche for social conservative women to write essays detailing how "feminism lied to us." Although certain famous feminists most certainly tell lies, I'm more inclined to blame our reading and viewing material from preventing us from putting down roots into reality.

It is a mistake, for example, to over-identify with the heroines of Regency romances. Pride and Prejudice's Mr. Bennett, who never had to work for a living, was the equivalent of today's multi-millionaire. Mr. Darcy was the equivalent of a 21st century billionaire. I'm unlikely ever to have seen a modern-day Elizabeth Bennett, unless she came north for the Knights of Malta Ball and bid for that jaw-droppingly expensive holiday on Gozo. Thinking we might be an Elizabeth Bennett of our time is an error for all whose photograph has not graced the pages of Country Life or Tatler.

I forget when I realised that it was a mistake to grow up always reading and studying books whose authors and characters think that having to work for your living (even if male, but definitely if female) is a brutal misfortune. That was as much as mistake as to think that people with the requisite brains and background are always blessed with high-status "careers" instead of jobs.

Meanwhile, I had a magical feeling that I would always be financially okay unless I got addicted to drugs. (All adults and Time magazine rubbed it in well that drugs were a one-way ticket to earthly hell.) And, generally speaking, I was usually (not always) financially (just) okay until I found myself asking an HR man from my husband's work how much money I would get if/when he died.

Guess what was the most traumatic episode of my life. Go on. Guess.

Listen up, prospective young--and current--SAHMs! If your husband is lying in hospital and it is very possible he will die in the next six months, you do not want to have conversations about money with strangers. Neither do you want to take papers to the hospital for your horribly ill husband to sign, so that you are not left homeless and destitute. And you also do not want to freak out that the postman left something that cost you £30 in the wrong place because you're still processing a financial trauma that happened five years before.

So you can reject feminism all you like and write splendid Tweets about how much you enjoy spending your days in the kitchen with your children cooking and then going out with them on nature walks, but I implore you to plan for your husband's eventual last sickness and death. Hopefully those sad things won't happen until he is 79.3+, but it could happen when he is 29. It could happen when he is 26. I once went to the funeral of a married man who died at 26. He had been married for only six months, and his unborn baby was due in five.

The fact is that your husband is going to die, and you don't know when. This is why you, the prospective SAHM who as yet does not have a husband, let alone dependent children, are going to LEARN A TRADE, and for the time being AVOID DEBT, GET A JOB, and SAVE SOME MONEY. You are also going to FIND OUT HOW MUCH LIFE COSTS, even if your parents have always sheltered you from this or told you that it's none of your business. (To dip a toe in the water, ask them/him/her how much the electricity bill is.) You are also going to READ BOOKS ON HOUSEHOLD FINANCE/FINANCIAL INDEPENDENCE.

When a young man you actually would fancy marrying begins to talk to you about marriage ("Would you ever consider marrying me?" is how one of my friends put it to his girlfriend), this is a good time to ask him if he thinks he can support a SAHM and a flock of children and, if so, how. (Incidentally, this is also a good time to bring up the adoption issue because not all men are keen on raising what they have traditionally called "other men's children.")

Hopefully the young man has a solid job or career plan. (If his marriage plan is to travel the world as a busker, ponder if you will still want to pass the hat when you're 9 months pregnant.) If he already has a job/career, then he should look into such things as health insurance and workplace pension plans and how they relate to his future wife and children. He should also, when he is young and in the pink of health, buy life insurance. Immediately after marrying, you must both make your wills. The first three months you are married, write down everything you spend so you can realistically create the backbone of a budget.

When you buy a home, make sure your name is on the deeds. Heck, make sure your name is on everything. This is not because you are a money-grubbing gold digger. It is because you have entrusted a man with your life and the lives of your future children and you are vulnerable. And it is also, by the way, because he is vulnerable. Men look all tough and strong but all kinds of dodgy cells are lurking in their hearts and brains and other places, biding their time to wipe them out and break your heart.

So to make this a handy list, the prospective SAHM must:

1. Learn a trade or profession to fall back on if her husband becomes terminally ill or simply dies.

2. Do this without going into large amounts of debt.

3. Use her pre-married life to get a job, get out of debt, and save as much as she can.

4. Learn how much life for young couples with children in her area costs. (Obviously 2 adults and a baby living in a one-bedroom flat in Dundee spend less on housing than 2 adults and a baby living in a townhouse in central Edinburgh.)

5. Read books on household finance/financial independence.

6. Ask suitors who have started to make marriage noises if they can afford to support a SAHM and, if yes, how.

7. Ask suitors how they would feel about adopting, should he and the prospective SAHM be unable to beget/conceive children. If this really is a deal-breaker (it wasn't for me), say so.

8. Encourage her fiancé to take out spouse-covering health insurance, join workplace pension schemes, and buy life insurance.

9. After marriage, make a will and encourage her husband to make a will.

10. Begin to record everything the couple spends so that they have enough data to make a workable budget.

11. When the couple buys a home, makes sure her name is on the deeds.

For my next post, I will offer advice for keeping your husband alive.

Thursday, 13 October 2022

Consolations during the Ordinary Form

|

| Random photo of Pope Francis I took. |

Sometimes I go to the Ordinary Form of the Mass, a more pleasant expression than "the Novus Ordo," words rarely typed with fondness. For me temptations to go to the OF instead of finding a Traditional Latin Mass usually involve convenience. There is an OF 15 minutes from my house and when travelling in rural areas it is much easier to find an OF than the TLM. The OF is also celebrated earlier in the day, and sometimes on Sunday evenings, or on Saturday evenings, so one is not tied to the time allotted to the TLM.

Everybody who goes to the TLM knows this, and the time and money spent getting to the TLM is a considered a worthy sacrifice. However, sometimes a Catholic feels compelled to sacrifice going to the TLM for some reason: to reserve the time to make a lunch for friends, to go on holiday. But sometimes I'm not sure that one's attendance at the TLM should be sacrificed to anything else, especially when going to Mass is thereby reduced to fulfilling an obligation.

The Prodigal Brother

One Sunday not too long ago, I elected to go to a local NO to give myself time to cook for a Sunday lunch party. Benedict Ambrose and our guests were all going to be at the Ordinariate Mass (aka the Personal Ordinariate of Our Lady of Walsingham in Scotland). Therefore, I went to the local OF, enjoying the short walk. I slipped into a pew rather near the back and cast an eye over the congregation. I was happy to see I was not the youngest person present. There was a man in his 30s, and I seem to recall two little children and maybe a few teens. The man closest to me was in his 80s, if not his 90s.

The Gospel was about the Prodigal Son, and the homilist's non-Scottish accent was so thick I--born and raised in a city of diverse accents--could only rarely understand him. It seemed no attempt had been made to encourage him to learn to pronounce English in a way intelligible to his flock. I did understand, however, that he felt that the real Prodigal Son was the unloving Older Brother and that the parable would have been different had the Sons' Mother been in the picture. He did not seem to say this as a Marxist critique of Our Lord's storytelling, but as forelock tug to feminism, or mothers, or women in general. Certainly the Older-Brother-was-the-real-Prodigal was a hat tip to current anti-tradition prejudices, not to mention a total pastoral deafness to the universal child's cry of "It's not fair!" The Father in the story, I recall, did not rip a strip off the hardworking, loyal, and hurt Older Brother but told him all that he had was his.

The hymns, with the shortbread tin exception of "Amazing Grace," were banal, childish, dated, and sung with great devotion by the elderly people around me. These were the hymns of their youth, I understood, and I shut my eyes and listened to them. I found this--not the songs, but the singing--consoling.

37 years of the Ordinary Form

I went every Sunday to the Ordinary Form from the Sunday after my birth until I met Benedict Ambrose, and it fostered my love of Catholics ourselves, the crowd to whom the priests spoke, and the crowd that answered the priest together. As the critics of the Novus Ordo point out, the congregation who faces the priest and the priest who faces the congregation create a closed circle, the Blessed Sacrament (and therefore God) shunted off to a side chapel or behind the priest's back. This is a terrible thing, but there is a silver lining: it fosters the congregation's affection for the priest and it fosters affection in the community for the community. As a romantic adolescent, I would beam at the slowly moving communion queue, for those people, friend and stranger alike, were all the Body of Christ.

It wasn't until I was in my twenties that the drawbacks of the Ordinary Form were pointed out to me--by an Anglican, who knew nothing of the Old Mass. I occasionally--and very much in the spirit of post-Vatican II Catholicism--joined this Anglican friend at one of the most beautiful, Oxford Movement inspired Anglican liturgies in the city. It was humiliating, but I digress.

My point is that just as people who go to the Ordinary Form (which is most of the minority of Catholics who go to Mass) take great pleasure from singing the hymns of their youth, I can find consolation in listening to their devotion. I recommend this to people who prefer the TLM but find themselves in an OF, an OF that they find distinctly unedifying.

If the priest tempts you to join the Donatists and there is no silence in which to redirect your attention to God, then throw yourself back into the love of those around you and into the admiration for their fidelity. Can there be any word but "faithful" for those who, Sunday after Sunday, scandal after scandal, return to their local church to pray privately in the brief silences, laugh together at the presider's jokes, repeat together the 50+ year old (or less) formulae, and sing the same--often terrible--hymns. At any rate, even if you argue with that, you must admit that these faithful are faithful to churchgoing.

There is a limit to how much consolation you can get from the congregation, however. Some Masses are celebrated so badly and with so much focus on the priest at the expense of God that it begins to feel like a sin not to have made the effort to get to the TLM.

"Is that enough?"

Catholics must go to Sunday Mass on pain of mortal sin. Most Catholics don't believe skipping Mass is a mortal sin--those would include the majority who do so every Sunday. However, I suspect a majority of the minority who DO go to Mass are propelled there, on some level, out of a sense of obligation, which is why liturgical abuse is also abuse of the Catholic laity. We are, as it were, a captive audience.

I think Steve Skojec, whose argument with the Church can be found elsewhere online, would agree with that. And the helplessness of the Catholic laity in our obligation came into my mind after the last Ordinary Form Mass I attended, which was in a small Scottish village.

Benedict Ambrose and I were on holiday and were, in fact, grateful that there was any Catholic church there at all. We walked to it in the splendid, sunny morning and sat down in a pew near the middle, making us the front row. Nevertheless, I did a quick scan and saw that there were many people younger than us, and eventually three children or so. At the front, to the right, was an elderly couple with a guitar, and it was quite easy to imagine that they had come there, Sunday after Sunday, since 1970 and to see them as 20 year olds overjoyed by "Pope Paul's Revolution."

The priest was late, having driven a fair distance from a city to substitute for the absent pastor. He processed up the aisle singing the hymn and told us from the altar that he was "Father [Diminuitive of Christian Name]" and then launched into an anecdote about his first visit to the region and how odd he had found the local dialect. He followed this up by mentioning his more recent and important connection to the district, and I will say this for him: he was perfectly comprehensible. I doubt anyone had to strain to understand him. Indeed, the problem was tuning him out.

The Gospel was about the Ten Lepers. The TLM community had this Gospel just a few weeks ago, and our priest, a noted scholar of the New Testament, had some very interesting and illuminating points to make about it. Sadly, I could not remember them all, so I hoped Father X would jog my memory with his own remarks.

Unfortunately, Father X was not particularly interested in the Gospel at all, aside from saying that one should not always go with the crowd and that Our Lord was a "majority of one." Instead, his stream of consciousness took him to an exciting family anecdote about the Second World War (in which, incidentally, his soldier-relation had intended to loot a private house) and then to Pope Francis and the (hopefully and reportedly untrue) story that the pontiff had, immediately after his election, repulsed the "ermine" mozzetta with the words "The carnival is over."

Father X was highly delighted by these words, which he evidently took as Gospel, and despite the look of horror that passed over the faces of the short front row in the middle, continued on to tell us about Pope Francis's delightfully savage remarks. Pope France had not, as Pope Benedict had, given Christmas presents to the Curia and slapped them on their backs (his words), but told them about their faults. Father X exulted in the many and various ways in which the pontiff had insulted these men, and then assured us he wasn't having a go at the hierarchy. He talked and talked, rambling, pausing for approving laughter, and I felt worse and worse. I attempted prayer, but Father X's delivery was such that prayer was impossible.

"Is he drunk?" I whispered to B.A.

B.A. thought and charitably whispered back that he thought Father X might be in the earliest stages of dementia.

And so it went for some time, until Father X, dentures flashing into a grin asked, "Is that enough?"

The congregation laughed politely, and Father X went to the altar to listen to the petitions of the faithful before putting his personal spin on the Liturgy of the Eucharist.

It was extraordinary. The words "Is that enough?" suggested that Father X really was just "filling in" for the absent pastor that that his homily was "filling in" what would otherwise have been dead space. By telling us his personal anecdotes and then what he thought were funny and improving anecdotes (and not, in fact, painful scandals) about Pope Francis, he thought he was doing us--or the missing priest--a favour. This leads me to the horrible thought that we, too, by going to the nearest Catholic church, were also just "filling in" what should have been our first consideration.

But there was in fact a consolation in that Mass, which was the sight of a quarter of a Sacred Host between the priest's fingers. The priest was neither quiet nor humble, but the Host was quiet and humble. The Host was patient, and the Host suffered Himself to be held by that ninny (for whom He had died) and the Host later suffered Himself to be placed on the unconsecrated hands of the faithful who queued up to receive Him.

Postscript

By the way, there are edifying examples of the Ordinary Form to be found in Scotland. It is possible to hear a very good homily, and one is given enough silence to pray, at Edinburgh's Saint Mary's Cathedral.

Thursday, 6 October 2022

The Sun from Behind a Cloud at Noon

My favourite photograph of Benedict Ambrose--with whom I fell in love 14 years ago today--doesn't look very much like him, mostly because it was taken when B.A. was only about 11 months old. He is seated on the carpet, wearing white baby shoes and blue dungarees and a red turtleneck of a very 1970s vintage. He has white-blond hair and sticky-out ears and big eyes that are so dark, you can't tell they're blue. However, this is the truest photo of Benedict Ambrose in existence because he looks so absolutely delighted to be alive. He is simply beaming at the camera.

I have another photograph of a beaming Benedict Ambrose, taken more than 40 years later. He doesn't like this photograph, and no wonder. He's lying in a hospital bed, he's got a large untrimmed beard shot with grey, and he has marks on his face from some fall or other--which is why I took the photo. It is likely that, when this photo was taken, he was so sick he was simply out of his mind. However, he was also absolutely delighted to see me.

So we have photos of the two extremes of B.A.'s life: the happy infant who has no idea about the troubles that may be in store for him in life, and the dangerously ill man who is deliriously happy his wife is there and otherwise doesn't have a clue. But both photos sum up what has always been so wonderfully attractive about Benedict Ambrose: his unusually sunny and sanguine disposition.

"Sometimes," B.A. would say to that.

"Usually," I reply.

And it's a wonderful gift to be married to an unusually sunny, sanguine, patient man, especially as an often stormy, pessimistic, and impatient woman. I can still call to memory outrageous offences against my dignity when I was four (for example, the future drug addict/criminal who mutilated my doll) whereas B.A. recalls (to me) very serious family betrayals without a whisper of a hint of resentment. In so far as a child ever "bounced back" from disappointments, B.A. actually did bounce. He was okay; he is okay.

In some very good ways, he's like a happy rubber ball. And this is extremely fortunate for me because on my snappish and snarly days, days in which I would most definitely hurt the feelings of a more sensitive man (or any of my relations), B.A. is not hurt but merely concerned because I seem to be unhappy. To really get on B.A.'s nerves, I have to throw myself on the floor and scream--which fortunately I haven't done for some time, and I bet you would have done it, too, given those particular circumstances, just saying.

Anyway, I (unsurprisingly) fell in love with this human sunbeam 14 years ago, and he (possibly more surprising, unless you knew about his ancient crush on Dame Emma Kirkby) fell in love with me, and it was like the sun coming out from behind a cloud around noon. It lit up the next fourteen years. It lit up the previous fourteen years. It was just one of those days (and weeks and months and years) that make unpleasant days and memories on either side pale and seem much more insignificant. We were so in love, we were probably actually insane, and our marriage would have been invalid if I hadn't got cold feet the day before the wedding and turned up in a very cautious, reflective mood.

Naturally it ruined my career as a professional Single, and I suppose--had I any brains--I would have had a super Seraphic Singles podcast by now (maybe in three languages!) and figured out how to counsel other Singles in the age of Swipe Right. However, I would rather have Benedict Ambrose and that's all there is to it.

What I can say about my pre-Benedict Ambrose writings about being Single is that it taught me to do my best to live a meaningful life as a Single. I believe that made me the kind of person I needed to be to be a happy married person. It certainly made me the person I needed to be to meet B.A. and appreciate him. So if you are Single and find this post vaguely depressing, contemplate that what you do NOW with your Singleness can contribute to your life LATER as a married person--if you marry, and in my experience, most Catholic Singles who want to marry eventually do.

Monday, 3 October 2022

Thin Red Line

The COVID pandemic is officially over, but as it happens, I now have COVID. That is, I have tested positive for COVID since Friday, and it's a real pain in the tuckus.

This fine word, by the way, is an anglicisation of the Yiddish "tuchus," which I probably heard in a 1980s Hollywood film rather than (as a Torontonian might expect) my parents' neighbourhood, where one is more likely to hear Russian or Hebrew, at least on the bus.

Or so I think. I have not actually been in my parents' neighbourhood since New Year's Day 2020.

The exact order if the set of circumstances that have led to my exile is a bit hazy now. A disease travelled out of China, and the Canadian government was very worried for the bad treatment of the Chinese by Canadians, but then a variation of the disease came out of the United Kingdom, so the Canadian government banned British flights between December 23 and January 7. Joyeux Noel!

Before that was a period where there weren't many flights from Britain anywhere--and while hiding in our homes and washing our groceries we hoped the atmosphere would profit from the break. The news out of Italy was terribly bad---although, when there were flights again, Benedict Ambrose and I had no trouble going there. It was before the vaccine, so all we had to do was not have a temperature. Going to Canada, once it lifted the anti-British ban, would have meant an expensive and possibly dangerous hotel quarantine. I seem to remember stories of forced van rides to undisclosed locations, bags of refuse, disgusting food, sexual assaults.

But life, especially expat life, got more difficult when there was a vaccine because Canadian families began to break up over the question of whether the vax was the best thing since sliced bread or the best thing since BEFORE sliced bread. It also meant, of course, that governments could decide to restrict travel (work, unemployment benefits, child visitation rights, etc.) only to people who had had the vaccine.

But some scientists and medical professionals were highly reluctant to take the vaccine. Some of them told my employer why, and occasionally I fixed their sentence structure and reduced the numbers of their exclamation points before we published their explanations. I also kept track of British COVID jab side effects reports, which made for gruesome reading.

It was almost, but not quite, illegal to tell people why other people were reluctant to take the vaccines, and my employer's readership skyrocketed because it was otherwise hard to find balanced reading. By balanced, I mean that most news websites told people to take the vaccines and our news website told them to not take the vaccines. If you read the government advice, and you read advice against the government advice, you read both sides of the story. That's what balanced means these days.

Naturally, working where I work, I did not take the vaccines.

(In Canada, a French-Canadian child told a talk show host that people like me should be reported to police. Another thought we should be deprived of this and that until we submitted.)

And I did not get sick. Oh, I had a bad tummy ache in August 2020, probably from an ice-cream sundae in rural Silesia, and I got the "super-cold" in April 2022, I think it was. That was pretty miserable, but I took a COVID test and COVID it was not.

So for most of the last 34 months I was healthy, happy, energetic, a danger to nobody, and I missed my family and friends back in Canada a lot.

(In case anyone has forgotten this already, until Saturday, October 1, 2022, unvaccinated Canadians could return to Canada from overseas--but would have to be in quarantine for 14 days and could not leave again.)

I missed my family and friends so much that when the Canadian truckers decided to protest Canadian COVID restrictions, I burst into tears. This will sound crazy if you read the Guardian instead of, you know, the Western Standard or the New York Times instead of the New York Post. However, I distinctly remember feeling that ordinary Canadian hockey dads, blue-collar, salt-of-the-earth, Tim-Horton's-coffee-drinking dads were going to set the country free so I could go home without being treated like a war criminal by airport staff and then--crucially--be permitted to leave the country again to rejoin my cancer-survivor husband.

This is not what happened, though. Instead the (government-subsidised) media turned on the Canadian hockey dads, and .... I don't want to live through that again, even in memory. However, even if the truckers failed, one Canadian dad did see an opportunity in the Freedom Convoy. Say hello, Canadian history, to Pierre Poilievre, the man whose total domination of the Conservative leadership elections led (can anyone doubt it?) to the end of the very probably illegal Canadian travel restrictions.

I waited for the pro-jab members of my family to come and see me, and eventually my elderly parents booked a tour of the Highlands and informed me that they would be along on October 1 to stay for six nights. I was terribly happy; Benedict Ambrose painted the master bedroom; we saved bottles of elderflower champagne for their delectation.

A week before, however, Benedict Ambrose felt like he had the flu and spent two days in bed. He was out of it again on Monday, but then I began to feel like I had the flu. I went to bed myself and stayed there until Thursday, when I felt well enough to do an honest day's work. However, B.A. and I decided that--just in case--we had better take COVID tests before Mum and Dad turned up to stay with us for a week. So appalled was I by the possibility that I might not be able to see my parents, I burst into frightened tears even before taking the test.

After taking the test, I was disconsolate.

So to wrap up this tale of terrible timing, we found Mum and Dad an AirBnB within walking distance of our home, and we bought a pile of £2 Tesco COVID tests so we can test ourselves every day. We meet my parents outside, keeping six feet apart, usually wearing masks. I feel utterly wretched leaving the house because, for the first time in 34 months, I am actually COVID-positive and, therefore, presumably dangerous to others. Naturally, B.A. and I stayed home from Mass.

I am not, however, particularly sick. Currently I cough from time to time, and I tire easily. Let's hope I'm over the worst. I chug Vitamin C, Vitamin D3, and zinc; I do not happen to have the exotic anti-malarial on hand.

And I feel happy because I have actually seen my Mum and Dad in person for two days in a row and because, no matter how much family members disagreed on the subject of COVID, the vaccines, and the truckers, we never broke up.